Hayward Gallery: Martin Creed 'What's the Point of it?' (until 27th April 2014)

I am speechless. I am confused. I am astounded. I am overwhelmed.

The grand spectacle currently being exhibited at the Hayward Gallery, SE1, comes courtesy of 2001's Turner Prize-winning artist, Martin Creed. In what appears to be something of a retrospective-to-date, the artist inundates his viewer with artworks coming from literally all angles. As there is strictly no photography or filming allowed inside the exhibition, I am apprehensive about how much I should reveal in this post, as there are some multi-sensory surprises that really should not be spoilt prior to visiting. Without a doubt, 'What's the Point of it?' is the most stimulating, exciting exhibition I have ever seen, and is a must-see fixture in London at the moment.

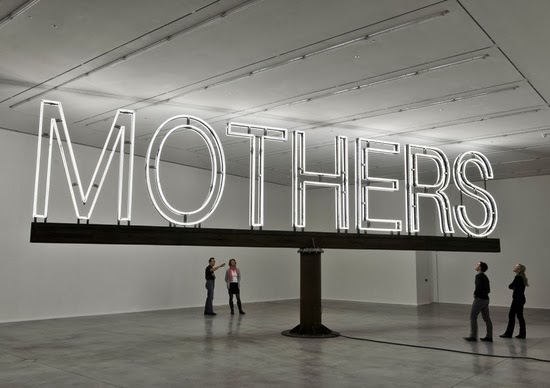

Having made notes while walking through, my sketchbook currently looks like I've just attended a lecture - believe me when I say there is so much to see at the Hayward, and additionally so much to say about each piece. Now, the first point of interest is the rotating neon light piece, 'Mothers'. Creed is clearly aware of the impact of first impressions, as he revels in the viewer fearing for their own safety, as the piece is perilously low; taller visitors will certainly need to be on their guard. As for deciphering the meaning of the piece, there are certainly a few dimensions, if you'll excuse the pun. The unwavering, bright lights depict the significant role that a mother has in all of our lives, whether that is in their presence or absence. Constant movement and low display seems to portray that they are an inescapable force and, regardless of physical stature, they will always make us, as their children, feel small. As a first piece, this definitely arouses excitement and anticipation in the viewer. However it is possible that this is largely due to the piece that surrounds this: 'Work No. 112 - Thirty-Nine Metronomes Beating Time, One at Every Speed', a sound piece that has, as the title confirms, thirty-nine metronomes maintaining a beat at different paces, which is both hypnotic and repellent at once. As I will elaborate, I can't help but wonder whether the gallery's invigilators have developed any symptoms of some sort of aural repetitive strain. Alas, the constant repetition builds a certain tension; personally Creed's art had an effect on me to the extent where I felt absolutely insane - I could not get imagery of Alice in Wonderland out of my head.

While some of his work is strongly reminiscent of the Young British Artists, there are also mainly similarities that can be made between Creed's work and various artistic movements. For example, 'Work No. 1253' strongly resembles work from Damien Hirst's 'Candy' collection (which I wrote about here) and his neon lighting pieces, 'Work No. 845 - Things' and 'Work No. 232' will remind many visitors of Tracey Emin. However 'What's the Point of it?' as a whole is so bewildering and chaotic that it prompts the viewer to wonder whether the artist is parodying both himself and the other influential artists in question. In addition to the three floors of gallery space occupied by Creed for this stint, there are three outdoor platforms that are utilised impressively and effectively. There is one in particular that is just the epitome of shock and surprise, which creates a fantastic effect, however I would not want to ruin this, so I implore you to visit the Hayward for yourselves. However one that I will mention is 'Work No. 1029', a black and white film featuring a man's penis gradually rising up, then back down. As expected, the piece leaves many visitors giggling helplessly like embarrassed schoolgirls, but my views and perspective were split between being (very mildly) impressed by the subject's ability to move in such a way (some older women around me were astounded: "that's not in real time, surely") and overwhelmed, as it is a large screen of nothing but a man's genitals immersed in the backdrop of the city that I love. Is it arousing? Not hugely. Despite its novelty, its display opens questions about social standards of public decency. Creed constantly entertains the ability to question what we as a society think is 'normal' or 'appropriate'. As he is clearly ambiguous and unsure of this himself, his work always looks as if it is in the process of 'becoming'. As a result, the viewer feels that they are on a certain level with the artist, as his work in one way or another certainly is relatable.

Speaking of genitals, (ahem) I feel that 'Work No. 960 - Cactus Plants', pictured below, deserves a mention. Here Creed presents thirteen consecutive cacti displayed next to eachother, in all different shapes, sizes and textures. As a phallic symbol, it is hardly mind-blowing to make the connection between this piece and the male sexual ego, but it is there and it is clear. A message being clear certainly does not make it less potent, and although this could be inferred as being amusing, it is a different outlook on sexuality and the aesthetics of such.

Apologies for the stream-of-conscious style in which this review has been written, but the rapid pace of the exhibition demands being communicated in such a way. The frantic way that Creed has used sound art throughout this exhibition is truly fascinating. 'Work No. 736 - Piano Accompaniment' employs a pianist playing some ascending, followed by descending, musical arpeggios on the instrument. This rather gimmicky example makes the exhibition suddenly feel like a sinister, atmospheric fairground. Wherever the viewer finds themselves, there is an accompanying soundtrack. (Even intermittent dog barking in the toilets - when you are not expecting it, I can tell you that it is nothing but terrifying) With lights, colours, sounds and even bodily functions being thrown at you from all angles, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain focus, but never so overwhelming as to break the hyperactive enthusiasm that exudes from each piece of art found at the Hayward Gallery, until its closure on 27th April, later in the year.

Personal highlight: The exhibition is full of excitement and surprises, but 'Work No. 1686 - Ford Focus' is an absolute treat.

"The more I work, the more I think I don't know what I'm doing" ~ Martin Creed

The grand spectacle currently being exhibited at the Hayward Gallery, SE1, comes courtesy of 2001's Turner Prize-winning artist, Martin Creed. In what appears to be something of a retrospective-to-date, the artist inundates his viewer with artworks coming from literally all angles. As there is strictly no photography or filming allowed inside the exhibition, I am apprehensive about how much I should reveal in this post, as there are some multi-sensory surprises that really should not be spoilt prior to visiting. Without a doubt, 'What's the Point of it?' is the most stimulating, exciting exhibition I have ever seen, and is a must-see fixture in London at the moment.

Having made notes while walking through, my sketchbook currently looks like I've just attended a lecture - believe me when I say there is so much to see at the Hayward, and additionally so much to say about each piece. Now, the first point of interest is the rotating neon light piece, 'Mothers'. Creed is clearly aware of the impact of first impressions, as he revels in the viewer fearing for their own safety, as the piece is perilously low; taller visitors will certainly need to be on their guard. As for deciphering the meaning of the piece, there are certainly a few dimensions, if you'll excuse the pun. The unwavering, bright lights depict the significant role that a mother has in all of our lives, whether that is in their presence or absence. Constant movement and low display seems to portray that they are an inescapable force and, regardless of physical stature, they will always make us, as their children, feel small. As a first piece, this definitely arouses excitement and anticipation in the viewer. However it is possible that this is largely due to the piece that surrounds this: 'Work No. 112 - Thirty-Nine Metronomes Beating Time, One at Every Speed', a sound piece that has, as the title confirms, thirty-nine metronomes maintaining a beat at different paces, which is both hypnotic and repellent at once. As I will elaborate, I can't help but wonder whether the gallery's invigilators have developed any symptoms of some sort of aural repetitive strain. Alas, the constant repetition builds a certain tension; personally Creed's art had an effect on me to the extent where I felt absolutely insane - I could not get imagery of Alice in Wonderland out of my head.

'Mothers' by Martin Creed

Image courtesy of www.hauserwirth.com

NB: The presentation of this piece at the Hayward is nothing like the image above

NB: The presentation of this piece at the Hayward is nothing like the image above

The second room, or space, that the exhibition holds goes from one bizarre, out-of-body experience to quite another. You may have already heard about Creed's controversial 'Sick Film', a video piece in which a sterile, white studio plays the backdrop to several people who simultaneously, in different shots, vomit on the floor. Needless to say, a difficult watch, especially as the video strangely makes the viewer want to follow suit; not in the sense of feeling ill, but doing so to feel refreshed and cleansed. (Many amusing comments were overheard throughout the exhibition; one boy, no older than ten years old, said: "mummy, isn't it ever so impolite") As installations go, it certainly is one of the more bizarre viewing experiences. Unfortunately for the weak-stomached viewers among us, sound effects from the film spread around the rest of the lower-level gallery, which eerily the viewer only notices once they have seen 'Sick Film'. However aside from this, just outside the viewing room, we are presented with 'Work No. 1421', a gold-plated bronze 'trophy' in the guise of a clenched fist. Creed's work is filled with confusion about the world, and how it makes us feel. While 'Sick Film' wants to make us come to terms with ourselves and what we are capable of, in both a positive and negative sense, his bronze sculpture shows defiance, strength and power of the tangible.

While some of his work is strongly reminiscent of the Young British Artists, there are also mainly similarities that can be made between Creed's work and various artistic movements. For example, 'Work No. 1253' strongly resembles work from Damien Hirst's 'Candy' collection (which I wrote about here) and his neon lighting pieces, 'Work No. 845 - Things' and 'Work No. 232' will remind many visitors of Tracey Emin. However 'What's the Point of it?' as a whole is so bewildering and chaotic that it prompts the viewer to wonder whether the artist is parodying both himself and the other influential artists in question. In addition to the three floors of gallery space occupied by Creed for this stint, there are three outdoor platforms that are utilised impressively and effectively. There is one in particular that is just the epitome of shock and surprise, which creates a fantastic effect, however I would not want to ruin this, so I implore you to visit the Hayward for yourselves. However one that I will mention is 'Work No. 1029', a black and white film featuring a man's penis gradually rising up, then back down. As expected, the piece leaves many visitors giggling helplessly like embarrassed schoolgirls, but my views and perspective were split between being (very mildly) impressed by the subject's ability to move in such a way (some older women around me were astounded: "that's not in real time, surely") and overwhelmed, as it is a large screen of nothing but a man's genitals immersed in the backdrop of the city that I love. Is it arousing? Not hugely. Despite its novelty, its display opens questions about social standards of public decency. Creed constantly entertains the ability to question what we as a society think is 'normal' or 'appropriate'. As he is clearly ambiguous and unsure of this himself, his work always looks as if it is in the process of 'becoming'. As a result, the viewer feels that they are on a certain level with the artist, as his work in one way or another certainly is relatable.

Speaking of genitals, (ahem) I feel that 'Work No. 960 - Cactus Plants', pictured below, deserves a mention. Here Creed presents thirteen consecutive cacti displayed next to eachother, in all different shapes, sizes and textures. As a phallic symbol, it is hardly mind-blowing to make the connection between this piece and the male sexual ego, but it is there and it is clear. A message being clear certainly does not make it less potent, and although this could be inferred as being amusing, it is a different outlook on sexuality and the aesthetics of such.

Apologies for the stream-of-conscious style in which this review has been written, but the rapid pace of the exhibition demands being communicated in such a way. The frantic way that Creed has used sound art throughout this exhibition is truly fascinating. 'Work No. 736 - Piano Accompaniment' employs a pianist playing some ascending, followed by descending, musical arpeggios on the instrument. This rather gimmicky example makes the exhibition suddenly feel like a sinister, atmospheric fairground. Wherever the viewer finds themselves, there is an accompanying soundtrack. (Even intermittent dog barking in the toilets - when you are not expecting it, I can tell you that it is nothing but terrifying) With lights, colours, sounds and even bodily functions being thrown at you from all angles, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain focus, but never so overwhelming as to break the hyperactive enthusiasm that exudes from each piece of art found at the Hayward Gallery, until its closure on 27th April, later in the year.

'Work No.960 - Cactus Plants' by Martin Creed

Image courtesy of www.theguardian.com

Personal highlight: The exhibition is full of excitement and surprises, but 'Work No. 1686 - Ford Focus' is an absolute treat.

"The more I work, the more I think I don't know what I'm doing" ~ Martin Creed