Suture at Niru Ratnam Gallery

2020 will surely be remembered, among other things, as the year in which every decision was a risk; that's not just coming from the hypochondriac in me, but from most angles on a global scale, there is an undoubted level of not only uncertainty but genuine peril in making life steps, both significant and naively inconsequential. Alas, it is always exciting to see new spaces pop up in the art world, and at a time where most people have not been seeing art in the flesh, I was very encouraged to see Soho's newest gallery in the form of Niru Ratnam Gallery, with its remit of focusing on artists of colour and women. I'm not entirely embarrassed to say that I wasn't really sure what 'Suture' meant prior to visiting the exhibition, but I do love me a loose theme so I decided to explore further. In the surgical world, a suture is a row of stitches holding together a surgical incision or wound (maybe this is already in everyone else's vocabulary, apologies if so!). However, from the gallery's press release we find a much more nuanced use of the term developed from theorists such as Stuart Hall: the way in which an individual is "sutured" into a discourse or culture that fits into a certain time or place in one's life, but is perhaps seen as labile, as an individual's identity develops and grows within a lifetime.

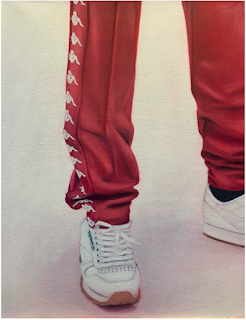

Lydia Blakeley, Classics, 2019. Oil on linen, 65cm x 50cm. Niru Ratnam Gallery, London.

So it was with this reading that I was interested to see the works of all three artists within this small group show: two of which I had seen before on numerous occasions (Jala Wahid and Lydia Blakeley) and another I had not (Kobby Adi). Thinking about the precariousness of the suture, and how one wrong or different action can cause the healing to rupture (see: mask wearing in public spaces!) is of great interest to me, especially when looking at the much-celebrated painting work of Lydia Blakeley. Her plain yet sophisticated-stylised works assess the everyday and hone in on the small details. 'Classics' is a great take on street style, and charmingly anonymising the wearer of the trainers, almost as a parody of the dehumanised extremes of materialism. While our taste in fashion undoubtedly tells others something about us, how surface-level and superficial is this analysis? Those who are well-read in fashion theory could certainly provide a better argument, but truthfully it's not really my bag (as it were).

I think one of the great draws to Blakeley's work, aside from it being incredibly realistic and the subject matter often charming, is its light and pleasingly banal nature. At a time where we are constantly forced to be doing instead of being, and feeling angry at the world, these warm works of art bring us back to slow living. In fact, with Blakeley you feel that the suture is secure, unless you happened to be personally triggered by the objectively unprovocative imagery.

Installation view: Jala Wahid, Exacting Revenge Like a Wayward Flame, 2019. Jesmonite, fiberglass and mica, 91cm x 40cm x 38cm. Niru Ratnam Gallery, London.

In a much more evocative direction we have the work of Jala Wahid, who graduated from Royal Academy Schools last year. I have been familiar with her work for a while now and I always find myself gravitating back to its unique textures and alluring colours, as they are a point of departure for themes of Kurdish identity and the female body as a site of resistance. The fitting of Wahid's three sculptures into the theme of 'suture' is the most beautifully done of the three artists, as with these works from 2019 we see three isolated pairs of legs frozen in time mid-dance. This includes 'Exacting Revenge Like a Wayward Flame' in a bright, fiery orange hue, which stands alongside 'Anger and Euphoria, One and the Same' in a similarly hot fuschia-red and 'Turning Fibre to Fire' in a more unusual pearly violet. Immortalised from an otherwise fleeting moment, Wahid's legs (of other women) are fully immersed in their Kurdish culture and, as the titles suggest, are incredibly powerful. The erasure and homogenisation of culture is an ongoing risk, and in gestures such as dance and visual art, Wahid shows us that culture is more than us as individuals, and things we find to be quotidian or even fun can be seen as resistance against cultural erasure.

Kobby Adi, for now, 2020. Pub mirror, fingerprints, non-reflective glass, sapele frame, 62cm x 41.6cm. Niru Ratnam Gallery, London.

For me, 'readymade' works are very much hit or miss, but Kobby Adi's 'for now' piece is my highlight of the exhibition. Its press release describes Adi's practice as "a subtle manipulation of signs and meanings" and this is certainly the case with this standout mixed media work, based on a pub mirror. Now that the Black Lives Matter has lovingly emboldened the public and institutions alike to bring down problematic monuments, the work could not be more perfectly timed. Here Adi depicts an almost blind celebration of a public figure ('Captain Morgan') whose past as a slave owner and sugar plantation owner in Jamaica conveniently gets forgotten in the branding of Captain Morgan, which is essentially a household name. As a globally recognised brand, the irony of rum being Jamaica's national drink is completely abhorrent. The pub mirror, which is cleverly non-reflecting, copious amounts of drinking provides us with a willing blindness to the reality of the world, much like attitudes to systemic racism; many are clearly of the belief that if it does not affect them personally, it cannot be as grave as others claim it to be. There is so much to unpack in what is a surface-level simple piece, it is a very exciting work and I will be following Adi's work hereafter to see how the research and messages manifest themselves visually.

Installation view: Niru Ratnam Gallery, Suture, 15 July - 29 August 2020.

Clearly, a lot of time and love has gone into 'Suture', which sounds like a cliché but when you see as much art as I do, the care really shows, and similarly it is also evident when artists have just been thrown together. The brewing rupture alluded to throughout the exhibition could really only have been done in 2020, in a year that started with the ongoing burning of Australian lands the size of South Korea, going into the dissolving of a section of the Royal family, one more murder at the hands of police brutality leading to the worldwide rupture of protests and a global pandemic further highlighting the ills of capitalism and, again, white supremacy. This is a time of monumental change, where we have all been forced to look at ourselves, look out for our communities in ways that, frankly, are alien to the neoliberal condition.

'Suture' has allowed me to deepen my own thinking into the fragility of culture on an individual level, but equally the strength cultures must have on a daily basis when affronted with the likes of gentrification, whitewashing and even artwashing. At a time where the cultural spheres are under immense pressure, it is great to see this new addition to London's scene; the gallery is open in real life but also has excellent documentation on their website, so it's also worth a look if you are based elsewhere or unable to travel at the moment. A superb return to gallery-hopping life, even as the art world's annual dry spell of August approaches.