Ed Atkins at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin

I made a concerted effort to see Ed Atkins' solo show as part of the fantastic Berlin Art Week, which ended on 18 September. Although of course the German capital is abuzz with culture and contemporary kunst the whole year through, I was particularly excited to explore this festival, and in particular its inclusion of a new body of work by Atkins, whose 2018 exhibition 'Olde Food' at London's Cabinet Gallery made a lasting impression on me.

Spanning across three spaces within the building, which holds onto its mystique from exterior to interior, the gallery showcases Atkins' new works in mixed media drawing, sound and video, creating an environment that fosters an intimate relationship between artist and viewer, given the personal and often tender topics addressed in the work. This is done through a technique that seems to exceed mere curation; the compelling dynamic of the art and the journey of the viewer leans more towards the choreographic.

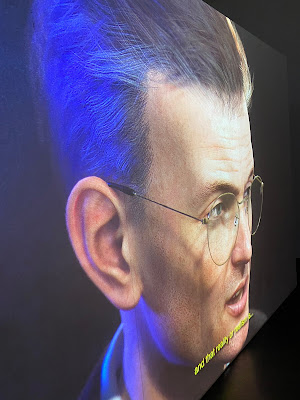

Arguably the most striking 'choreographic' element can be found in the display of 'The worm'. Projecting onto a surface that squeezes the room into such an acute angle that the audience are already made to feel rather physically awkward is a fascinating move. Although at first jarring, once the video work begins, we understand this contortion, as the subject matter leads us towards the theme of family. As if one's own family politics are not sufficiently complex, we are thrown into another, via an animated depiction of a phone conversation between the artist and his mother. This swings between feeling extraneously itchy, and heartfelt, earnest and relatable.

Anyone who has encountered Atkins' work before will immediately recognise his trademark style in the animated video piece. Whilst the artist's mother, on the other end of the phone line, is not visually represented, Atkins' responses are visible on screen, using face and motion capture technology to present his animated self. The marriage of the recognisable, everyday, perhaps hyper-real aesthetic, with sinister undertones is what makes Atkins not only a popular artist, but one whose work becomes compulsive viewing. A casual gallery visitor may begrudge the fourteen-minute duration of 'The worm', but once one has found a vaguely comfortable angle from which to watch the film, it is hard to break away.

A sense of being uncomfortable runs through the show. In the case of 'The worm', voyeurism abounds as the viewer impedes upon a private conversation between the artist and his mother. She tells stories of inherited low self-esteem, epitomising inter-generational pain and anguish which is escalated, yet critically muffled, by a combination of British stiff upper lip and enforced silence, enabled through suspected sexism and classism. It all feels very intimate, and suddenly witnessing Atkins' mother's story in her own words feels like a therapeutic breaking of the stigma cycle.

While 'The worm' adjoins the front and the back of the gallery, the mixed media drawings displayed in the first space are also of interest, and certainly undeserving of being ignored in favour of the multi-sensory pull of the video works. The first space houses two works, of a foot and a shoe respectively, both 'Untitled', comprised of quink (Parker Pen ink), bleach and coloured pencil. They evoke a sense of incompleteness, being almost comically redundant in isolation. At the point of experiencing these works, we can already hear 'Love', played nearby, a fourteen-minute sound piece involving the artist singing, which also feels quietly unnerving.

At the end of the corridor, we find a more traditional viewing space for a moving image artwork. A white cube-style room accommodates a wooden bench facing 'Voilá la vérité', a recent, shorter video piece that accentuates the artist's versatility. As a reworking of 'Ménilmontant', a silent film released in 1926, the contemporary piece shows a young woman sat on a bench, quietly sobbing and lamenting lost memories. An older man sits next to her and begins to share small fragments of his lunch. These actions and gestures of unspoken, vastly minimised emotional expression and sharing (perhaps scarce) resources with one another feels rather alien to a contemporary viewer, especially a city dweller and amidst a pandemic. In experiencing the work, our own sense of loss from the inescapable movement of time feels palpable.

'Voilá la vérité' and 'The worm' come together in their refusal to overtly scrutinise inter-personal relationships. Artificial intelligence was used to master the former, while computer-generated animation and motion capture technologies have been employed in the latter, yet what we witness is the reproduction of real, human feelings. More technologically-minded people may argue that this is exactly how these softwares function; if tech produced exclusively alien visuals, audiences would neither trust nor engage with them. Atkins' solo show at Isabella Bortolozzi, whilst on the surface is dedicated to the lineages of emotion, transpires to become an investigation of the insidious mediation of technology within said lineages. It does so in a way that is so vibrant and compelling that, as an audience, we are almost fully hypnotised into its hypothesis.