uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things at Liverpool Biennial

On the occasion of the opening of the city's Biennial, I spent a few days in arguably one of the UK's best cities, Liverpool, and was reminded of the importance of both the sensory and spatial readings of 'place'. The historical and contemporary statuses, and legacies, of a place somehow converge and become very powerful in our own perceptions. Alas, the vibrancy and vivaciousness of Liverpool lends itself well to hosting a major cultural event (see: Eurovision last month), and certainly has its own character which is a product of its history and present moment. The theme of this year's biennial comes from the isiZulu language; its title is uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things, and its first word translates as "spirit, breath, air, climate, and wind", reinforcing the human impact of the themes being discussed and illustrated through the artworks.

In addition to producing a written archive of that which I observed and contemplated, a motivation to document my time in Liverpool comes from an urge to respond to a review by The Telegraph's chief art critic, Alastair Sooke, whose final paragraph (spoiler alert!) concludes that "engaging with such difficult and desperate history is at risk of becoming curatorially, and even artistically, conventional". Aside from the slight gritted-teeth cringe of taking the word "curatorially" too seriously, it is disheartening, to say the least, to see anti-racist, decolonial practices reduced to such a critique in what is an impactful but fairly uncontroversial showing in Liverpool. In the review, Sooke also name-drops the Black Lives Matter movement, which although particularly activated in 2020, has been protesting brutality towards Black people since 2013. Unlike so many movements in the, dare I say, "conventional" history of art, BLM and its anti-racist legacy is not representative of a mere phase; besides, the Biennial's curator, Khanyisile Mbongwa, introduces the programme as "a call for ancestral and indigenous forms of knowledge, wisdom, and healing...pulling threads from East and Southern Africa, East and South Asia, North and South America, the Middle East, Oceania, and Europe".

To put this particular point to bed, any genuine concern for the "conventional" need turn its attentions towards the oft-reviewed, oft-revered arts institutions of the UK, where anyone with little to no engagement with modern art would be forgiven for believing that there were no more than a dozen artists in existence. Andy Warhol or Michael Craig-Martin, anyone?

One commendable aspect of the showcase is the re-activating of Mersey architecture. It is challenging to navigate acknowledgments of architectural sites in colonial, violent histories, but shying from the challenge is no longer an option. Tate Liverpool and Tobacco Warehouse at Stanley Dock are two shining examples of this. The latter is an interesting and incredibly atmospheric space, and one that produces a certain degree of frustration in terms of accessibility and engagement outside of the art world and its followers, given its location some way out of the city centre, with a metro ride followed by a somewhat grim walk along a motorway to find it. However the ambience of that which awaits could not be more different, with an inherent reverence which feels tangible, almost heavy. Rarely is this felt more than in Binta Diaw's Chorus of Soil installation, a re-imagining of the 18th century Brooks slave ship, delicately comprised of soil and seeds at almost 1:1 scale.

The confrontation of Chorus of Soil is, again, difficult, epecially given Diaw's detail of using their medium to outline how each individual's body would have been situated in the ship. Part of what makes our current historical moment so "difficult", and by proxy anxiety-inducing, is that we are aware of an immense volume of violent and criminal injustices from the past and present. Again: facing these horrors is something we can no longer opt-out of, and in showing ignorance towards events such as the slave trade, and their legacies, we leave ourselves open to history repeating itself. That is one reason why Chorus of Soil is so powerful; there is almost no room for discussion beyond what we are being shown.

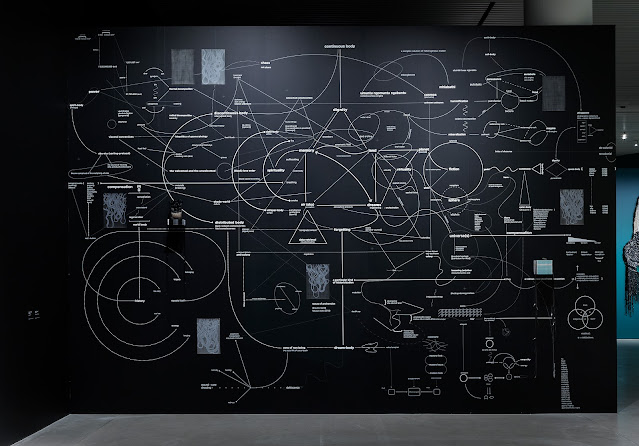

Over at Royal Albert Dock is Tate Liverpool, which has its own links to slavery. Its offering differs slightly to the other locations in the programming, in that the institutional stakes are higher, and as such, production value follows suit. Let's not pretend that this is a wholly unpleasant experience, but it does at times feel at odds with uMoya's messaging. While curator Mbongwa says, "I curate because I do not know, and because of my unknowing, I am asked to forensically and ancestrally listen," the model of the institution traditionally provides a top-down pedagogical model. Conceptual critique aside for one moment, the Tate's contribution to the Biennial is rather unmissable, boasting works that are not only thought-provoking but truly feel world-class. Examples include Bologna-based Rwandan artist Francis Offman's installation of Bibles held up with callipers, a brutal, sharp tool which we learn were used by Belgian colonisers to measure the faces of Rwandan people to classify them into racial groups. Like most of the works, they are not especially Instagrammable, and require luxurious slow looking and consideration. Another that will potentially appeal most to the academic art lovers is South African artist Nolan Oswald Dennis' work, No conciliation is possible. It is hard to speak of its power; taking up a whole wall space, the piece is text-based and diagrammatic, speaking to "a Black consciousness of space", with a vast range of themes linked, such as 'mnemonic field', 'land archive' and 'ancestors'. It is a process, a poetry, an invitation.

During its opening weekend, there was very little buzz about the Liverpool Biennial, presumably partly because it fortunately continues until mid-September, but also art world attention, and attendance, was mostly based in Switzerland for Art Basel. The latter's focus is sales and showboating, so the gravity and humanity shown at Liverpool Biennial was not only refreshing, but also necessary. Using the word 'urgent' always feels misguided when talking about art, as we must always be realistic of its potential to be genuinely socially mobilising, but messages and cultures that stray from the West-centric structures and gazes make the 2023 Liverpool Biennial a rewarding and worthwhile experience, which is only accentuated with the reciprocal gift of your attention.

.jpg)